In the fall we want to return to the fireside, but we are looking for more than warmth. We are drawn to the ancient idea of the hearth. For centuries the hearth brought families together. But a fire is no longer the heart of a home and its loss has dispersed the family. We can trace the retreat of the hearth.

We once lived with smoke and fire. When we moved indoors, we moved the campfire indoors. In the Medieval manor, an open fire burned near the center of a large hall. The smoke was left to rise up to the second story and out a hole in the roof. The fire drew air from open doors. Birds flew through. In time, in an effort to clear the smoke from the hall, the hearth was moved to one side and placed under a hood.

The fireplace replaced the hood. The open fire was now enclosed on three sides. Fireplaces were usually big, more like a fire room. Some fireplaces had benches inside. In Colonial America, the kitchen fireplace could be eight feet wide and three or four feet deep. The cook would walk to the back of the fireplace to use the brick bake oven. (In other designs the brick oven is alongside the big hearth.) Most of the heat went right up the chimney. As in the Medieval hall, doors were left open to feed the fire and move the smoke out of the room.

Houses were cold. Snow sifted through the windows, water froze in pitchers, ink froze in inkwells, well-pump handles froze and wells froze. Empty back chambers kept Thanksgiving pies “fresh and good” until April’s violets, advised Harriet Beecher Stowe.

In diaries of the 18th and early 19th Century New England, the hearth is not the welcoming emblem of home-feeling, the happy family circle bathed in firelight. It is, rather, a big messy beast that must be fed and fed, returns little heat and is prone to lashing out and taking sacrifices. Houses burned down, herbs and flax drying by the hearth caught fire, children fell into fireplaces or were scalded to death by big kettles of water. The losses from fire run like a swift, tragic river through the old town histories. The hearth is a mercurial god.

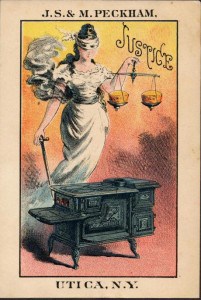

The hearth needed discipline. The fireplace shrank, and it disappeared. In the 1790s, the scientist Count Rumford designed a shallow, small fireplace which pushed more heat into the room and effectively drew the smoke up the chimney. For the first time a fire would actually warm a room. Rumford’s design was brilliant, but it was the last hurrah for the downsized hearth. Woodstoves, gaining acceptance in the 1840s, ended the reign of the campfire. Smoke and fire had been separated, and the fire hidden in a cast-iron box.

The boxed-fire still held the household in its orbit. Only the kitchen cookstove fire was kept going through the winter, a practice that lasted into the 1930s in the countryside. The rest of the house was cold and dark. A fire would only be set in the sitting room for guests. Candles were a luxury. Much of life was lived in the cold and shadows.

Keeping warm kept the family together – everyone in the kitchen – mom sewing or reading, dad figuring or fixing tools, children doing homework or playing games, aunts, uncles, grandparents all in the mix. It was wonderful some say – we sang, we told stories, we read the Bible aloud. It was horrible others say – we fought, we got in each other’s way. All joy and grief was condensed into one room.

Winter’s grip was broken by central heating and electricity. Fire was exiled to a furnace in the cellar. The campfire had learned indoor manners. It had been tamed. Electric motors were now the lungs of the house, circulating heat from the unseen fire.

The central furnace and the electric light freed the family, dispersing men, women and children to their own semi-autonomous regions in the home. More heat and light equals more space. Heat was the gravity of the old household. Once the fire is exiled, it’s as if gravity is repealed. The size of houses grows steadily as families shrink. Shared dinners are fewer and the happy family is lost in space.

A home without a hearth was unmoored. It was a tent with its central pole removed. Once the hearth is extinguished, just what is a home? An answer can be read in the origins of the words for hearth. Hearth is derived from the Old English heorp for the place where the fire is set on the ground. (Oerp in Old English – ground, earth.) Our houses were losing the connection between fire and earth. Focus is Latin for hearth. Our houses were losing focus. The house has been un-hearthed. We dwell in electricity – we dwell in what it makes possible: noise and image.

A revolution has taken place. Fire has journeyed from the center to the cellar. Putting out a campfire that’s burned through the millennia is such a significant change that we can divide the history of dwelling between Hearth and Post Hearth. Tell me how you heat your house or make your breakfast and I’ll tell you how you dwell.